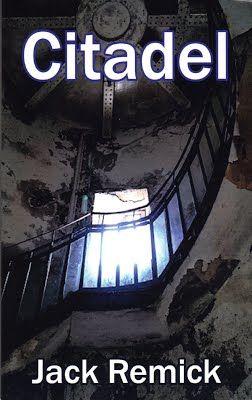

Women’s literary fiction

Publisher: Quartet Global Books

Irven DeVore, an evolutionary biologist, writes that "Males are a breeding experiment run by females." What if, in fact, women ran everything? What if women rejected the culture of rape and violence to take control of their lives in the safety of the Citadels? What if women could exist without males? CITADEL is a metafictional, apocalyptic story braided into a contemporary post-lesbian novel built on genetics.

Advance Praise

"I loved the book and I'm suggesting it to all the writers, editors and women I know as a must read. You blew me away... the book drew me in completely... great experience!

I'm not sure how you managed to come up with this... let alone research it... a story usually follows one or two Characters... I found myself following the writer, the editor, the publisher, not to mention the Characters in the book... and never got lost, never ended up wondering who someone was or why they did that? I read the book in short spurts and longer chunks depending on opportunity... but never had a problem of falling back into the story... you had me from page one to the end. Great job" -- Wally Lane, filmmaker, screenwriter.

Interview

What is the

hardest part of writing your books?

My thinking is that

writers have only three problems: how to start, how to keep going, how to

finish. For some people, finishing is the hard part; for others, it’s how to

keep going; still others get lost and tangled up in the beginning. I have not

had much trouble with any of the three because I write using a timer/stop watch

and start lines. Before I ever write a scene in a novel, I do a lot of what I

call “Writing about the Writing.” This is a technique similar to what the

screenwriters call a “treatment,” but without the focus. Using the writing

about the writing, using the timer, and the start line (I talk about this

later) I get going. Sometimes I have no idea who or what the novel is about.

For example, Citadel. When I started Citadel I had a character, but a character

with no name. She was holed up in a motel in the California desert. I didn’t

know why she was there or what she was doing. But I kept writing. After a month

or so of writing about the writing, I had a name for the character, I had her

backstory, I had the objects she had brought to the motel—a cell phone, a

computer, a manuscript—and a gang of personal problems. The next questions

were: what’s on the computer? and who does she talk to? why has she run to the

motel? As you can see, I had started. To keep going I connected Trisha to other

characters while I worked out their story arcs in the same way. Once I had the

characters in place, once I had their backstories written out, I thought about

writing scenes. But where to start the scene writing? Turns out that Tricia

likes to go to the beach, so I opened there:

“As far back as I can remember, I’ve had a sense of dread. I dream,

and when I wake, I am sure it will be the day the world ends. Rose, my

therapist, tells me more of her clients have apocalyptic dreams like mine. She

doesn’t know what it means.

Yesterday at the beach as I watched the beach meat in their

combat ritual, I had one of my visions of annihilation.”

At that

point, I used another technique borrowed from the screenwriters called “Cut

To.” It’s simple. It goes like this:

Citadel

opens in a scene called Beach Meat.

Cut to:

Trisha drives Daiva back to the condo.

Cut to:

Trisha gets Daiva’s manuscript, Citadel.

Cut to: at

Pinnacle Books, Trisha sends a copy of Citadel to the cloud.

Once I have

all the scenes worked out in the cut-to sequence, I’m ready to write any scene

at any time. That’s to keep going.

To finish

sometimes requires a couple shots at the ending. But to finish, you have to

have an ending. I worked with a woman who had written dialogue for The Pink

Panther movies. She said that Blake Edwards, director of that series, always

worked from the ending back to the beginning using this technique: Okay, here I

am, how did I get here? As you can see, this is the Cut-to technique in

reverse. So, all writers need to answer one of two questions: What comes next

(cut to) or what happened just before. How did I get here?

Once you

have an ending, you are free then to think about rewriting the opening—and you

will because rewriting is the neglected stepchild of the novelist. There is a

complete difference between “rewriting” and “editing.” Most writers think

rewriting means start on page one and make changes until you get to the ending.

Mostly what produces is a mess you hire a professional to clean up.

To go back

to the three problems, you can see that there is a complete process that keeps

you involved in the novel from the first word to the last. In that process, the

problems disappear. Advice? Write about the writing before you ever tackle a

scene.

What

songs are most played on your Ipod?

I’m one of

the troglodytes who doesn’t own an Ipod. My music listening is still CD based

and aimed at the classics. Having been, in my early life, a pianist, I’m very

fond of piano so spend time searching out new, technically based pianists who

are bringing fresh interpretations of the standards to light.

Do

you have critique partners or beta readers?

I work with

other writers two days a week. Our process is to write scenes or sections

longhand, work them up on a word processor the work the pieces aloud together.

Most of my writing is done longhand in sessions Natalie Goldberg calls “writing

practice.” I find that this is the most efficient way for me to write—using

this generic “start line—”Today I’m writing about. If I’m in the middle of

work, I know that what will come will be related to the work but not always.

The freedom to work this way lets your hand follow your mind without focus. Far

from “free-form” or “free writing”, the generic line lets your character talk

and dictate to you so that they control you rather than you controlling them.

Sometimes the results are astounding, sometimes just plain flat writing, but

always of interest. In the partnered group, we read the pieces. This is the

best way to break out of writer’s solitude—hearing your work for the first time

makes you not just the writer but part of a greater audience.

What

books are you reading now?

I just

finished “Hers to Protect,” a novel by Nicole Disney. Nicole is an inspired and

inspiring young novelist who says that she writes novels with lesbians in them

but she doesn’t write lesbian novels. “Hers to Protect” is a powerhouse, a tour

de force in genre writing which does in fact have lesbian characters, but it’s

a police/crime novel focused on gangs, drugs, and, of course, the lesbian

relationship. I recently read and reviewed Eleanor Parker Sapia’s “A Decent

Woman.” This is a terrific novel set in Puerto Rico at the turn of the

Twentieth Century. I’m about to dig into “Sex at Dawn” a 2010 release subtitled

‘How We Mate, Why We Stray, and What It Means for modern relationships.’ I like

to move around through the writing universe—sometimes focusing on anthropology,

then genetics before moving on to history and essays.

How

did you start your writing career?

I was

young, lost, and living in South America. I wanted to be a pianist, so had enrolled

at the Conservatorio Nacional de Musica in Quito. I composed a few pieces for

piano, but then started reading Spanish/Ecuadorian poetry and from there

launched into the English poets. I then met a couple of poets, David Bartine,

Jack Moody, and Jorge Bravo Munoz who encouraged my poetry but also suggested

that I break out and write fiction. Breaking into fiction took a lot longer

than I thought it would. My first short story, “Frogs” came out in Carolina

Quarterly. I was writing, but had no technique, didn’t know what I was doing. I

wrote a short novel called “The Stolen House,” which Jim Villani, the publisher

of Pig Iron Magazine out of Youngstown, Ohio liked and published. Because he

liked the novel, Jim suggested that I write for Pig Iron. For eight years I

wrote a fifty page novella every four months for Pig Iron. A few years later, I

met Robert J. Ray and Natalie Goldberg. I wrote The Weekend Novelist Writes a

Mystery with Ray and under Natalie’s influence wrote eight novels, six of which

were published by Catherine Treadgold at Coffeetown Press in Seattle.

I am working on a set of essays titled “What Do I Know?”

‘Wisdom in the Twenty-first Century.’

About the Author

Jack Remick is the author of twenty books—novels, poetry, short stories, screenplays. He co-authored The Weekend Novelist Writes a Mystery with Robert J. Ray. His novel Gabriela and The Widow was a finalist for the Montaigne Medal as well as a finalist in Foreword Magazine’s Book of the Year Award. He reviews for the New York Journal of Books. He is a frequent guest and co-host on Michigan Avenue Media with Marsha Casper Cook. His novel Citadel, was featured in the July issue of the Australian magazine eYs.

Contact Links

Purchase Links

Thanks for the very interesting interview. I love photographing architecture, so I love that cover.

ReplyDeletesherry @ fundinmental

thanks for hosting

ReplyDelete